Operation Wetback

Operation Wetback was an immigration law enforcement initiative created by Joseph Swing, a retired United States Army lieutenant general and head of the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS). The program was implemented in June 1954 by U.S. Attorney General Herbert Brownell.[1] The short-lived operation used military-style tactics to remove Mexican immigrants—some of them American citizens—from the United States. Though millions of Mexicans had legally entered the country through joint immigration programs in the first half of the 20th century, with some being naturalized citizens and some once native, Operation Wetback was designed to send them to Mexico.[2]

The program became a contentious issue in Mexico–United States relations, even though it originated from a request by the Mexican government to stop the illegal entry of Mexican laborers into the United States. Legal entry of Mexican workers for employment was at the time controlled by the Bracero Program, established during World War II by an agreement between the U.S. and Mexican governments. Operation Wetback was primarily a response to pressure from a broad coalition of farmers and business interests concerned with the effects of illegal immigration from Mexico.[3] Upon implementation, Operation Wetback gave rise to arrests and deportations by the U.S. Border Patrol.

Background and causes

[edit]Migration and labor before World War II

[edit]

Mexico began discouraging emigration to the United States in the early 1900s, beginning with President Porfirio Díaz.[4] Diaz, like many other Mexican government officials, realized that the laborers leaving for the United States would be needed to industrialize and expand the Mexican economy.[4] While Mexico did not have extensive capital, its largest asset was abundant, cheap labor, the primary resource needed to modernize the country's economy and develop industrial agribusiness.[5]

The large and growing agricultural industry in the United States created a demand for labor. From the 1920s onward, with the exception of the depression era, Mexicans served as the primary labor source for much of the agricultural industry in the United States, especially in the Southwest.[5] Every year during the 1920s, some 62,000 workers entered the United States legally, and over 100,000 illegally.[6]

Pressure from Mexican agribusiness owners to return laborers from the United States to Mexico prompted increased action by the Mexican government. The labor problems caused crops to rot in Mexican fields because so many laborers had crossed into the U.S.[7] Meanwhile, American agriculture, which was also transitioning to large-scale farms and agribusinesses, continued to recruit illegal Mexican laborers to fulfill its expanding labor requirements.[8]

The Bracero Program (1942–1964)

[edit]

During World War II, the Mexican and American governments developed an agreement known as the Bracero Program, which allowed Mexican laborers to work in the United States under short-term contracts in exchange for stricter border security and the return of illegal Mexican immigrants to Mexico.[9] Instead of providing military support to the U.S. and its military allies, Mexico would provide laborers to the U.S. with the understanding that border security and illegal labor restrictions would be tightened by the United States.[10] The United States agreed, based upon a strong need for cheap labor to support its agricultural businesses, while Mexico hoped to utilize the laborers returned from the United States to boost its efforts to industrialize, grow its economy, and eliminate labor shortages.[11]

The program began on September 27, 1942, when the first braceros were admitted into the United States under this agreement with Mexico.[12] The program called for braceros to be guaranteed wages, housing, food, and exemption from military service.[13] However, even though this was the agreement promised by the United States, conditions were imposed by Mexico that only healthy young men with agricultural experience who could show a permission letter stating that they were not needed in Mexico were eligible, and workers who did not fit this requirement were denied paperwork to work in America.[14]

The Bracero Program would not have a consistent implementation or direction during its 22-year duration.[15] The program itself can be classified into three main phases. The first between 1942 and 1946 saw heavy input from the Mexican government in regard to the operations of the Bracero Program.[15] The second phase was between 1947 and 1954 when the policy shifted from mass legalization of illegal immigrants to mass repatriation of said immigrants.[15] The El Paso incident would begin discussion of establishing a labor pool versus dealing with the "illegal invasion" of these immigrants.[15] In certain cases, undocumented workers found by INS agents would be legalized as Braceros instead of deported. The final phase lasted from 1955 to 1964 and thus saw the end of the Bracero Program.[15] The paradoxical nature of wanting a source of labor in the form of Mexican immigrants but distaste for the immigrants by the population would persist in the United States.[15]

After this agreement was reached, the Mexican government continued pressuring the United States to strengthen its border security or face the suspension of the legal stream of Mexican laborers entering the United States.[7] In October 1948, Immigration officials opened the Texas–Mexico border which allowed several thousand undocumented workers to cross the border.[15] From here most workers were escorted by Border Patrol agents straight to the cotton fields.[15] This event started the informal practice of using undocumented Mexican labor while the blacklist was in place. This incident was problematic due to the direct way the US government was involved in the managing and movement of these undocumented workers.[15] This opening of the border was also in direct violation of previous agreements with the Mexican government.[15] This incident would become known as the El Paso incident.[16] Two million Mexican nationals participated in the Bracero program during its existence, but tensions between the program's stated and implicit goals,[17] plus its ultimate ineffectiveness in limiting illegal immigration into the United States, eventually led to Operation Wetback in 1954.[11]

Illegal migration after 1942

[edit]Despite the Bracero program, American growers continued to recruit and hire illegal laborers to meet their labor needs.[18] The program could not accommodate the number of Mexicans who wished to work in the United States. Many who were denied entry as a bracero crossed illegally into the United States in search of better wages and opportunity.[19] Nearly 70% of people who were attempting to immigrate to America were denied because they were viewed as undesirable for a variety of reasons, including age, gender, or other factors.[20] While the Mexican Constitution allowed citizens to cross borders freely with valid labor contracts, foreign labor contracts could not be made in the United States until an individual had already legally entered the country.[4] This conflict, combined with literacy exams and fees from INS formed significant obstacles for Mexican laborers wishing to seek higher wages and increased opportunities in the United States.

Food shortages were common in Mexico while most of the foodstuff produced was exported. Hunger and misgovernment, combined with population growth, prompted many Mexicans to attempt to enter the United States, legally or illegally, in search of wages and a better life.[21] This growth was exponential, resulting in the population nearly tripling in a short time period of forty years.[20] The Mexican government's interference with the privatization and mechanization of Mexican agriculture added more problems to finding employment in Mexico, providing yet another reason for Mexicans to enter the United States in search of higher wage jobs.[5] With the growing concern about unassimilated immigrants, and the diplomatic and security issues surrounding illegal border crossings, popular pressure caused the INS to increase its raids and apprehensions beginning in the early 1950s leading up to Operation Wetback.[22] The Korean War and the Red Scare also prompted tighter border security to prevent presumed communist infiltration.[23]

Mass deportations also affected the growing patterns in California and Arizona; although the United States had promised farm owners additional Bracero labor.[24] During the Bracero program, "an estimated 4.6 million workers entered America legally, while other immigrants that were turned away still entered" because of the work opportunities occurring in the southwest.[2] California then became dependent on the workers while Texas continued to hire workers illegally after this was banned by the federal government; however, because of the agricultural demand, this was overlooked.[2] While both countries were benefitting from this program in different ways, the large influx of immigration caused Eisenhower to end the program with Mexico.

Border control leading up to Operation Wetback

[edit]In 1943 more United States Border Control Officers were posted along Mexico's northern border.[25] Pressure from well-connected Mexican land and farm owners frustrated with the Bracero program prompted the Mexican government to call a meeting in Mexico City with four agencies of the United States government: the Department of Justice, the Department of State, the INS, and the Border Patrol.[26] This meeting resulted in increased border patrol along the United States–Mexico border by the United States, yet illegal immigration persisted.[26] One of the main issues was that increased pressure by the Mexican government produced more deportations, but the deported Mexicans rapidly reentered the United States. To combat this, the Mexican and American governments developed a strategy in 1945 to deport Mexicans deeper into Mexican territory by a system of planes, boats, and trains.[27] However, in 1954, negotiations surrounding the bracero program broke down, prompting the Mexican government to send 5000 troops to its border with the United States.[28]

In correspondence with assistants to President Dwight Eisenhower, Harlon Carter, head of the Border Patrol, planned Operation Cloud Burst, which requested an executive order to mobilize the military to round up illegal entrants at the southwestern border and to raid migrant camps and businesses in the interior of the United States. In deference to the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, Eisenhower declined to authorize the use of Federal troops, instead appointing Army General Joseph May Swing as the commissioner of the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[29][2] Eisenhower gave Swing the power to resolve border control issues in order to stabilize labor negotiations with Mexico.[30]

Operation Wetback (1954)

[edit]Implementation and tactics

[edit]| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Chicanos and Mexican Americans |

|---|

At its peak, the Bracero program allotted around 309,000 contracts to Mexican laborers. What followed was a series of repatriations under the name Operation Wetback. Similar repatriations can be seen during the Great Depression.[15] Operation Wetback was a program of massive apprehensions and deportations aimed at undocumented Mexican nationals, by the U.S. Border Patrol and alongside the Mexican government.[31] Planning between the INS, led by Gen. Joseph Swing as appointed by President Eisenhower and the Mexican government, began in early 1954 while the program was formally announced in May 1954.[32] Harlon Carter, then head of the Border Patrol, was a leader of Operation Wetback.[33]

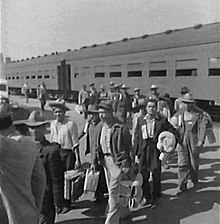

In June, command teams of 12 Border Patrol agents, buses, planes, and temporary processing stations began locating, processing, and deporting Mexicans who had illegally entered the United States. A total of 750 immigration and border patrol officers and investigators; 300 jeeps, cars and buses; and seven airplanes were allocated for the operation.[34] Teams were focused on quick processing, as planes were able to coordinate with ground efforts and quickly deport people into Mexico.[35] Those deported were handed off to Mexican officials, who in turn moved them into central Mexico where there were many labor opportunities.[36] While the operation included the cities of Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Chicago, its main targets were border areas in Texas and California.[35]

Overall, there were 1,074,277 "returns", defined as "confirmed movement of an inadmissible or deportable alien out of the United States not based on an order of removal" in the first year of Operation Wetback.[37] This included many workers without papers who fled to Mexico fearing arrest; over half a million from Texas alone.[38] The total number of sweeps fell to just 242,608 in 1955, and continuously declined each year until 1962, when there was a slight rise in apprehended workers.[39] Despite the decline in sweeps, the total number of Border Patrol agents more than doubled to 1,692 by 1962, and an additional plane was added to the force.[39]

During the entirety of the Operation, border recruitment of illegal workers by American growers continued, due largely to the low cost of illegal labor, and the desire of growers to avoid the bureaucratic obstacles of the Bracero program. The continuation of illegal immigration, despite the efforts of Operation Wetback, along with public outcry over many US citizens removed, was largely responsible for the failure of the program.[40] Because of these factors, operation Wetback lost funding.[2]

The program resulted in a more permanent, strategic border control presence along the Mexico–United States border.[41]

Timeline

[edit]| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| June 9 | California roundup and deportation begins[15] |

| June 10 | Phase One Arizona-California, Operation: Buslift

First Greyhound bus leaves El Centro, California bound for Nogales, Arizona. On board are detainees from the San Francisco regional detention center and roadblock inspection captures. 28 buses transport 1,008 migrants to Arizona where they will be transferred into the interior of Mexico.[15] |

| June 17 | Phase Two of California to Arizona, Operation: Sweeps

The Agricultural regions of Arizona and Southern California become primary sweep targets. INS authorities employ the aid of farmers to reveal undocumented workers.[15] |

| June 17–26 | Through the assistance of local police, 4,403 people are rounded up. 64% of them were working in non-agricultural jobs.[15] |

| June 20 | Sweeps continue throughout the Central Valley of California through bases set up in Fresno and Sacramento.[15] |

| June 24 | Bill 3660 and Bill 3661 are proposed in both houses of Congress with the intent to dissuade employers and smugglers from employing/bringing in illegal immigrants. Neither bill passed.[15] |

| July 3 | The first mobile task force is dispatched in McAllen, Texas. Their goal was to set up roadblock inspections, inspect trains, and dissuade any migrants from heading north.[15] |

| July 15 | First day of complete operation in Texas with a focus on the Lower Rio Grande Valley.[15] |

| September 3 | First deportation by sea. The SS Emancipation and SS Vera Cruz sail the 2,000-mile voyage from Port Isabel, Texas to Veracruz, Mexico a total of 26 times. Both ships transport around 800 illegal immigrants per voyage.[15] |

| September 18 | First airlift from Midwest begins. The deportees in Chicago are transported to Brownsville, Texas. More airlifts arrive from Kansas City, Saint Louis, Memphis and Dallas. From here, the deportees are sent to Veracruz by sea.[15] |

Consequences

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (September 2022) |

The name "wetback" is a slur applied to illegal entrants who supposedly entered the United States by swimming the Rio Grande.[42] It became a derogatory term applied generally to Mexican laborers, including those who were legal residents.[43] Similarly, the 1855 Greaser Act was so-known based on the anti-Mexican slur "greaser".

One of the biggest problems caused by the program for the deportees was sending them to unfamiliar parts of Mexico, where they struggled to find their way home or to continue to support their families.[44] More than 25% of apprehended Mexicans were returned to Veracruz on cargo ships, while others were transported by land to southern cities in Mexico.[45] Those apprehended were often deported without receiving the opportunity to recover their property in the United States, or to contact their families prior to deportation.

Deportees often were stranded without any food or employment when they were released in Mexico.[46] Deported Mexicans sometimes faced extreme conditions in their country; 88 deported workers died in the 112 °F (44 °C) heat in July 1955.[35] Another issue was repeated illegal border crossings by those who had been previously deported; from 1960 through 1961, repeaters accounted for 20% of the total deportees.[39] Certain U.S. Border Patrol agents practiced shaving heads to mark repeat offenders who might attempt to reenter the United States. There were also reports of beating and jailing chronically offending illegal immigrants before deporting them.[47] While most complaints concerning deportation were undocumented, there were more than 11,000 formal complaints (about 1% of all actions) from documented bracero workers from 1954 through 1964.[48]

Operation Wetback was the culmination of more than a decade of intensifying immigration enforcement. Immigration enforcement actions (removals and returns) rose rapidly from a low of 12,000 in 1942, to 727,000 in 1952, the final year of the Truman Administration. Enforcement actions continued to rise under Eisenhower, until reaching a peak of 1.1 million in 1954, the year of Operation Wetback. Enforcement actions then fell by more than 90 percent in 1955, and 1956, and in 1957 were 69,000, the lowest number since 1944. The number of enforcement actions rose again in the 1960s and 1970s, but did not exceed the 1954 peak of Operation Wetback until 1986.[37]

At the same time that immigration enforcement was expanding in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the Bracero program was also rapidly expanding legal opportunities for Mexican laborers. Although it began as a wartime measure, the Bracero program saw its largest expansion after the war. The number of wartime braceros peaked at 62,000 in 1944, but the number began to rise again in the late 1940s, and reached its peak in 1956, when the program gave temporary work permits to 445,000 Mexican workers.[49]

See also

[edit]- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Immigration to the United States

- Operation Gatekeeper

- Mexican Repatriation

- Repatriation flight program

- United States v. Brignoni-Ponce (1975)

- Wetback (slur)

- Emigration from Mexico

References

[edit]- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 421–44.

- ^ a b c d e Blakemore 2018.

- ^ Koulish 2010.

- ^ a b c Hernandez 2006, p. 425.

- ^ a b c Hernandez 2006, p. 426.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 131.

- ^ a b Hernandez 2006, p. 430.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 127–30.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 138–39.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 139.

- ^ a b Hernandez 2006, p. 428.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 138.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 139, 143.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 425

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Mize & Swords 2011, p. [page needed].

- ^ "El Paso incident". immigrationtounitedstates.org. Retrieved November 13, 2024.

- ^ Calavita 2010, "Foreword".

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 147–48.

- ^ a b Cabrera 1994.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 426–28.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 152–53.

- ^ Astor 2009, pp. 5–29

- ^ Gonzales 2009, p. 177.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 429.

- ^ a b Hernandez 2006, pp. 429–30.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 430–31.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 433.

- ^ Hernández 2010, p. 183.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 444.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 442.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 441–42.

- ^ Associated Press 1954.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 155.

- ^ a b c Ngai 2004, p. 156.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 441–44.

- ^ a b Homeland Security 2015 Yearbook.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 156–57.

- ^ a b c Ngai 2004, p. 157.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 152, 158–60.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 157–60.

- ^ On the Issues 2015

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 149.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, p. 443.

- ^ Ngai 2004, pp. 156, 160.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 160.

- ^ Hernandez 2006, pp. 437–39.

- ^ Ngai 2004, p. 143.

- ^ Rural Migration News 2006.

Sources

[edit]- "Border Police in Drive on Wetbacks". Sarasota Journal. Associated Press. June 17, 1954. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Braceros: history, Compensation". Rural Migration News. Vol. 12, no. 2. April 2006.

- "Table 39. Aliens Removed Or Returned: Fiscal Years 1892 To 2015". 2015 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Department of Homeland Security.

- Astor, Avi. ″Unauthorized Immigration, Securitization, and the Making of Operation Wetback.″ Latino Studies 7 (2009): 5–29.

- Blakemore, Erin (March 23, 2018). "The Largest Mass Deportation in American History". History. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Cabrera, Gustavo (1994). "Demographic Dynamics and Development: The Role of Population Policy in Mexico". Population and Development Review. 20: 105–120. doi:10.2307/2807942. ISSN 0098-7921. JSTOR 2807942.

- Calavita, Kitty. Inside the State: The Bracero Program, Immigration, and the I.N.S. Reprint edition (originally published by Routledge, 1992). New Orleans: Quid Pro Quo Books, 2010.

- Gonzales, Manuel G. (2009). Mexicanos: A History of Mexicans in the United States (2nd ed.). Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-22125-4.

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle (2006). "The Crimes and Consequences of Illegal Immigration: A Cross Border Examination of Operation Wetback, 1943–1954". Western Historical Quarterly. 37 (4): 421–444. doi:10.2307/25443415. JSTOR 25443415.

- Hernández, Kelly Lytle (2010). Migra!: A History of the U.S. Border Patrol. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25769-6.

- Koulish, Robert (2010). Immigration and American Democracy: Subverting the Rule of Law. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203883228. ISBN 978-1-135-84331-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mitchell, Don. They Saved the Crops: Labor, Landscape, and the Struggle over Industrial Farming in Bracero-Era California. Geographies of Justice and Social Transformation Series. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2012.

- Mize, Ronald L.; Swords, Alicia C.S. (2011). Consuming Mexican Labor: From the Bracero Program to NAFTA. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-0157-4. JSTOR 10.3138/j.ctt2ttpgc.

- Ngai, Mae M. (2004). Impossible Subjects: Illegal Aliens and the Making of Modern America. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07471-9.

- "Dwight Eisenhower on Immigration". On the Issues. August 18, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Ballinger, Matt. "From the archives: How The Times covered mass deportations in the Eisenhower era". Los Angeles Times.

- Copp, Nelson Gage (1971). 'Wetbacks' and Braceros: Mexican Migrant Laborers and American Immigration Policy, 1930–1960. San Francisco. OCLC 329634.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dillin, John (July 6, 2006). "How Eisenhower solved illegal border crossings from Mexico". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- García, Juan Ramon (1980). Operation Wetback: The Mass Deportation of Mexican Undocumented Workers in 1954. Westport, CT: Greenwood. ISBN 0-313-21353-4.

- Scruggs, Otley M. (1988). Braceros, 'Wetbacks', and the Farm Labor Problem: Mexican Agricultural Labor in the United States, 1942–1954. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-5145-9.

- Law enforcement operations in the United States

- History of immigration to the United States

- History of Mexican Americans

- Presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower

- Illegal immigration to the United States

- Mexico–United States relations

- Forced migrations in the United States

- Anti-Mexican sentiment in the United States