Soviet ruble

| Pубль (Russian) 14 other official names

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| ISO 4217 | |||||

| Code | SUR | ||||

| Unit | |||||

| Plural | rubli (nom. pl.), rubley (gen. pl.) | ||||

| Symbol | руб or р (in Cyrillic) Rbl/Rbls[1][2] or R[3] (in Latin) | ||||

| Denominations | |||||

| Subunit | |||||

| 1⁄100 | kopeck (копейка) | ||||

| Plural | |||||

| kopeck (копейка) | kopeyki (nom. pl.), kopeyek (gen. pl.) | ||||

| Symbol | |||||

| kopeck (копейка) | коп. or к. in Cyrillic kop., cop. or k (in Latin) | ||||

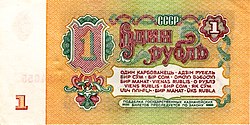

| Banknotes | Rbl 1, Rbls 3, Rbls 5, Rbls 10, Rbls 25, Rbls 50, Rbls 100, Rbls 200, Rbls 500, Rbls 1,000 | ||||

| Coins | 1 kop, 2 kop, 3 kop, 5 kop, 10 kop, 15 kop, 20 kop, 50 kop, Rbl 1, Rbls 3, Rbls 5, Rbls 10 | ||||

| Demographics | |||||

| Date of introduction | 1922 | ||||

| Replaced | Imperial Russian ruble | ||||

| Date of withdrawal | 1992–1994 | ||||

| Replaced by | see below | ||||

| User(s) |

| ||||

| Issuance | |||||

| Central bank | State Bank of the Soviet Union | ||||

| Printer | Goznak | ||||

| Mint | Leningrad (1921–1941; 1946–1991) Krasnokamsk (1941–46) Moscow (1982–1991) | ||||

| This infobox shows the latest status before this currency was rendered obsolete. | |||||

The ruble or rouble (/ˈruːbəl/; Russian: рубль, romanized: rubl', IPA: [rublʲ]) was the currency of the Soviet Union. It was introduced in 1922 and replaced the Imperial Russian ruble. One ruble was divided into 100 kopecks (копейка, pl. копейки – kopeyka, kopeyki). Soviet banknotes and coins were produced by the Federal State Unitary Enterprise (or Goznak) in Moscow and Leningrad.

In addition to regular cash rubles, other types of rubles were also issued, such as several forms of convertible ruble, transferable ruble, clearing ruble, Vneshtorgbank cheque, etc.; also, several forms of virtual rubles (called "cashless ruble", безналичный рубль) were used for inter-enterprise accounting and international settlement in the Comecon zone.[5]

In 1991, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Soviet ruble continued to be used in the post-Soviet states, forming a "ruble zone", until it was replaced with the Russian ruble in September 1993.

Etymology

[edit]The word ruble is derived from the Slavic verb рубить, rubit', i.e., 'to chop'. Historically, a "ruble" was a piece of a certain weight chopped off a silver ingot (grivna), hence the name.

The word kopeck or copeck (in Russian: копейка kopeyka) is a diminutive form of the Russian kop'yo (копьё)—a spear. The reason for this is that a horseman armed with a spear was stamped on one of the faces of the coin. The first kopeck coins, minted at Novgorod and Pskov from about 1534 onwards, show a horseman with a spear. From the 1540s onwards the horseman bears a crown, and doubtless the intention was to represent Ivan the Terrible, who was Grand Prince of all Russia until 1547, and tsar thereafter. Subsequent mintings of the coin, starting in the eighteenth century, bear instead Saint George striking down a serpent.

Ruble in the Soviet Union

[edit]

The Soviet currency had its own name in all the languages of the Soviet Union, often different from its Russian designation. All banknotes had the currency name and their nominal printed in the languages of every Soviet Republic. This naming is preserved in modern Russia; for example: Tatar for 'ruble' and 'kopeck' are сум (sum) and тиен (tiyen). The current names of several currencies of Central Asia are simply the local names of the ruble. Finnish last appeared on 1947 banknotes since the Karelo-Finnish SSR was dissolved in 1956.

The name of the currency in the languages of the fifteen republics, in the order they appeared in the banknotes:

| Language | In local language | IPA transcription | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ruble | kopeck | ruble | kopeck | |

| Russian | рубль | копейка | [ˈrublʲ] ⓘ | [kɐˈpʲejkə] ⓘ |

| Ukrainian | карбованець | копійка | [kɐrˈbovɑnet͡sʲ] ⓘ | [koˈpijkɐ] ⓘ |

| Belarusian | рубель | капейка | [ˈrubʲɛlʲ] | [kaˈpʲɛjka] ⓘ |

| Uzbek | сўм | тийин | [som] | [tijin] |

| Kazakh | сом | тиын | [swʊm] | [tɪjən] |

| Kyrgyz | сом | тыйын | [som] | [ˈtɯjɯn] |

| Tajik | сӯм | тин | [sɵm] | [tin] |

| Georgian | მანეთი | კაპიკი | [manetʰi] | [kʼapʼikʼi] |

| Azerbaijani | манат | гәпик | [mɑnɑt] | [ɡæpik] |

| Turkmen | манат | көпүк | [mɑnɑt] | [kœpʏk] |

| Lithuanian | rublis | kapeika | [ˈrʊbɫɪs] | [kɐˈpɛɪkɐ] |

| Latvian | rublis | kapeika | [ˈrublis] | [ˈkapɛika] |

| Estonian | rubla | kopikas | [ˈrublɑ] | [ˈkopikɑs] |

| Finnish | rupla | kopeekka | [ˈruplɑ] | [ˈkopeːkːɑ] |

| Romanian | рублэ/rublă | копейкэ/copeică | [ˈrublə] | [koˈpejkə] |

| Armenian | ռուբլի | կոպեկ | [ˈrubli] | [ˈkɔpɛk] |

Note that the scripts for Uzbek, Azerbaijani, Turkmen and gradually Kazakh have switched from Cyrillic to Latin since the breakup of the Soviet Union. Moldovan has switched to Latin and is once again referred to as Romanian.

These fifteen names derive from four roots:

- Slavic verb рубить, rubit', "chop"

- Turkic root som, "pure"

- Latin monēta, "coin"

- Old Ruthenian karbuvaty, "carve", "emboss", "mint"

Historical Soviet rubles

[edit]First Soviet ruble (paper), 1917–1922

[edit]The first ruble issued for the Soviet government was a preliminary issue still based on the previous issue of the ruble prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. They are all in banknote form and started their issue in 1919. At this time other issues were made by the white Russian government and other governing bodies. During that time, the Russian economy suffered from hyperinflation.

Denominations were as follows: 1, 2, 3, 5, 10, 15, 25, 50, 60, 100, 250, 500, 1,000, 5,000, 10,000, 25,000, 50,000, and 100,000 rubles. Short-term treasury certificates were also issued to supplement banknote issue in 1,000,000, 5,000,000, and 10,000,000 rubles. These issue was printed in various fashions, as inflation crept up the security features were few and some were printed on one side, as was the case for the German inflationary notes.

Banknotes: In 1918, state credit notes were introduced by the RSFSR for 1, 3, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000 rubles. These were followed in 1919 by currency notes for 1, 2, 3, 15, 20, 60, 100, 250, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000 rubles, and in 1921 with notes for 5, 50, 25,000, 50,000, 100,000, 1,000,000, 5,000,000, and 10,000,000 rubles were added.

Gold ruble (chervonets), 1921–1924

[edit]

Upon launch of the New Economic Policy in 1921 came efforts to revive as currency and accounting unit the pre-war gold standard ruble, equal to 1⁄10 of a chervonets (with Rbls 10. equal to 8.602 g of 90% fine gold, then equal to US$5.14).[6] The gold ruble existed in parallel with the paper ruble of 1917–1922, which continued to depreciate versus the former, climbing to 50 billion paper rubles per gold ruble in March 1924.

Coins: The first coinage after the Russian Civil War was minted in 1921–1923 according to pre-war Czarist standards, with silver coins of 10, 15 and 20 kopecks minted in 50% silver, 50 kopecks ("poltinnik" or 1⁄2 ruble) and 1 ruble in 90% silver, and 10 rubles (one chervonets) in 90% gold. These coins bore the emblem and legends of the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic) and depicted the famous slogan, "Workers of the world, Unite!". These coins would continue to circulate after the RSFSR was consolidated into the USSR with other Soviet Republics until the discontinuation of silver coinage in 1931.

Third Soviet ruble, 1 January 1923 – 6 March 1924

[edit]The third Soviet ruble was issued equal to 1,000,000 paper rubles of 1917–1922, simply to handle the unwieldiness over the number of digits in the first currency. Again it continued to depreciate versus the gold ruble until the latter climbed to Rbls 50,000 in 1924. Only paper money was issued, in the form of state currency notes in denominations of 50 kopecks and 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1,000, 5,000, and 10,000 rubles.

In early 1924, just before the next redenomination, the first paper money was issued in the name of the USSR, featuring the state emblem with six bands around the wheat, representing the languages of the then four constituent republics of the Union: Russian SFSR, Transcaucasian SFSR (Azerbaijani, Armenian, and Georgian), Ukrainian SSR and Byelorussian SSR. They were dated 1923 and were in denominations of 10,000, 15,000, and 25,000 rubles.

Fourth Soviet ruble, 7 March 1924 – 1947

[edit]After Joseph Stalin's consolidation of power following the death of Lenin, a final redenomination occurred which replaced all previously issued currencies. The fourth Soviet ruble was equal to 50,000 rubles of the third issue, or 50 billion paper rubles of the first issue, and began at par with the gold ruble (1⁄10 chervonets). It built on the stability in the exchange value of the third ruble which happened towards the end of 1923.[6]

Coins began to be issued again in 1924, while paper money was issued in rubles for values below 10 rubles and in chervontsy for higher denominations. No chervontsy were issued in gold, just decrees on the parity of circulating rubles with the gold ruble, which already failed to take hold as early as 1925.

Coins, 1924–1961

[edit]

In 1924, copper and silver coins were again minted to pre-war Czarist standards, in denominations of 1⁄2, 1, 2, 3 and 5 kopecks in copper, 10, 15 and 20 kopecks in 50% silver, and 50 kopecks and 1 ruble in 90% silver. From this issue onward, the coins were minted in the name of the USSR (Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics). The "Workers of the World" slogan was carried forward. Coins issued 1921–1923 representing the gold ruble continued to circulate at par with this post-1924 ruble.

Copper coins were minted in two types; plain edge and reeded edge, with the plain-edged types being the fewest in number. The 1 Rbl coin was only issued in 1924, the poltinnik (or Rbl 1⁄2) was issued 1924–27, and the denga (or 1⁄2 kop) was issued from 1925 to 1928. In 1926, smaller aluminium-bronze coins were minted to replace the large copper ones (1 to 5 kopecks), but were not released until 1928. The larger coins were then melted down.

Stalin failed to maintain the ruble's value versus the gold ruble as early as 1925, and by 1930 its value even struggled to stay above the melt value of the silver 10-, 15- and 20-kopeck coins. Soviet authorities scapegoated "hoarders" and "exchange speculators" as responsible for the shortages, and confiscatory measures were taken. In 1931, the remaining silver coins were replaced with redesigned cupro-nickel coins depicting a male worker holding up a shield which contained the denominations of each. All silver coins were to be returned and melted down.

In 1935, the reverse of the 10-, 15- and 20-kopeck coins were redesigned again with a simpler Art Decor-inspired design, with the obverse of all denominations also redesigned, having the "Workers of the world, unite!" slogan dropped. The change of the obverse designs did not affect the smaller coins immediately, as some 1935 issues bore the "Workers of the World" design while some bore the new "CCCP" design. The state emblem also went through a series of changes between 1935 and 1957 as new Soviet republics were added or created, this can be noted by the number of "ribbons" wrapped around the wheat sheaves. This coin series remained in circulation during and after the monetary reform of 1947 and was finally discontinued in 1961.

In August 1941, the wartime emergency prompted the minting facilities to be evacuated from the Neva district in Moscow and relocated to Permskaya Oblast as German forces continued to advance eastward. It only became possible to resume coin production in the autumn of 1942, for one year the country was using coins made before the war. Furthermore, the coins were made of what had suddenly become precious metals – copper and nickel, which were needed for the defense industry. This meant many coins were being produced in only limited quantities, with some denominations being skipped altogether until the crisis finally abated in late 1944. These disruptions led to severe coin shortages in many regions. Limits were put in place on how much change could be carried in coins with limits of 3 Rbls for individuals and 10 Rbls for vendors to prevent hoarding as coins became increasingly high in demand. Only high inflation and wartime rationing helped ease pressure significantly. In some instances, postage stamps and coupons were being used in place of small denomination coins. It was not until 1947 that there were finally enough coins in circulation to meet economic demand and restrictions could be eased.

Banknotes, 1924–1947

[edit]In 1924, state currency notes were introduced for 1, 3, and 5 gold rubles (рубль золотом). These circulated alongside the chervonets notes introduced in 1922 by the State Bank in denominations of 1, 3, 5, 10 and 25 chervontsy. State Treasury notes replaced the state currency notes after 1928. In 1938, new notes were issued for 1, 3 and 5 rubles, dropping the word "gold".

| 1938 Series | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Denomination | Obverse | Reverse |

|

Rbl 1 | Miner | |

|

Rbls 3 | Soldiers | |

|

Rbls 5 | Pilot | |

|

1 чрв | Lenin | |

|

3 чрв | ||

|

5 чрв | ||

|

10 чрв | ||

Fifth Soviet ruble, 1947–1961

[edit]Following World War II, the Soviet government implemented a confiscatory redenomination of its currency (decreed on December 14, 1947) to reduce the amount of money in circulation. The main purpose of this change was to prevent peasants who had accumulated cash by selling food at wartime prices from using this to buy consumer goods as the postwar recovery took hold.[7] Old rubles were revalued at one tenth of their face value. This mainly affected paper money in the hands of private individuals. Amounts of Rbls 3,000 or less in individual private bank accounts were not revalued, while salaries remained the same. This revaluation coincided with the end of wartime rationing and efforts to lower prices and curtail inflation, though the effects in some cases actually resulted in higher inflation. Unlike other reforms, this one did not affect coins.

Banknotes

[edit]In 1947, State Treasury notes were introduced in denominations of 1, 3 and 5 rubles, along with State Bank notes for denominations of 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles. The State Bank notes depicted Lenin while the Treasury notes depicted floral artistic designs. All denominations were colored and patterned in a similar fashion to late Czarist notes.

In 1957, all these notes were reissued with the old date but modified design: following the abolition of the Karelo-Finnish SSR, the number of ribbons on the state emblem was reduced from 16 to 15, and the nominal in Finnish was removed from the obverse.

| 1947 Series | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Denomination | Obverse | Reverse |

| Rbl 1 | State Emblem of the Soviet Union | ||

|

Rbls 3 | ||

|

Rbls 5 | ||

|

Rbls 10 | Vladimir Lenin | |

|

Rbls 25 | ||

| Rbls 50 | |||

|

Rbls 100 | Moscow Kremlin | |

Sixth Soviet ruble, 1961–1991, (Identified as ISO code SUR)

[edit]The 1961 redenomination introduced 1 new ruble equal to 10 old rubles and restated all wages, prices and financial records into new rubles. It differed from the confiscatory nature of the 1947 reform when banknotes were reduced to 1⁄10 of their value but wages and prices remained the same.[8] Its parity to the US dollar underwent a devaluation, however, from US$1 = 4 old rubles (0.4 new ruble) to US$1 = 0.9 new ruble (or 90 kopecks). It implies a gold parity of Rbls 31.50 per troy ounce or Rbl 1 = 0.987412 gram of gold, but this exchange for gold was never available to the general public. Banknotes and coins of this series were designed by Ivan Dubasov.

Coins

[edit]

The 1958 pattern series: by 1958, plans for a monetary reform were underway and a number of coin pattern designs were being experimented with before implementation. The most notable of these was the 1958 series, in denominations of 1, 2, 3 and 5 kopecks in copper-zinc, and 10, 15, 20 and 50 kopecks and 1, 3 and 5 rubles in copper nickel. These coins all had the same basic design and became the most likely for release. Indeed, they were mass-produced before the plan was scrapped and a majority of them were melted down. During this time, 1957 coins would continue to be restruck off old dies until the new coin series was officially released in 1961. This series is considered the most valuable of Soviet issues due to their scarcity.

On 1 January 1961, the currency was revalued again at a rate of 10:1, but this time a new coinage was introduced in denominations of 1, 2, 3 and 5 kopecks in aluminium-bronze, and 10, 15, 20 and 50 kopecks and 1 ruble in cupro-nickel-zinc. Like previous issues, the front featured the state arms and title while the back depicted date and denomination. The 50-kopeck and 1-ruble coins dated 1961 had plain edges, but starting in 1964, the edges were lettered with the denomination and date. All 1926–1957 coins were then withdrawn from circulation and demonetized, with the majority melted down.

Commemorative coins of the Soviet Union: in 1965, the first circulation commemorative ruble coin was released celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Soviet Union's victory over Nazi Germany, during this year the first uncirculated mint-coin sets were also released and restrictions on coin collecting were eased. In 1967, a commemorative series of 10-, 15-, 20- and 50-kopeck and 1-ruble coins was released, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Russian Revolution and depicted Lenin and various socialist achievements. The smaller bronze denominations for that year remained unchanged. Many different circulation commemorative 1-ruble coins were also released, as well as a handful of 3- and 5-ruble coins over the years. Commemorative coins from this period were always slightly larger than general issues; 50-kopeck and 1-ruble coins in particular were larger, while the 1967 series of the small denominations were the same circumference but thicker than general issues.

Initially, commemorative rubles were struck in the same alloy as other circulating coins until 1975, when its composition was changed to higher-quality copper-nickel with zinc excluded. Its specifications (31 mm diameter, 12.8 grams) were nearly identical to those of the 5-Swiss franc coin (31.45 mm, 13.2 g, cupronickel) worth approx. €4.39 or US$5.09 as of August 2018, resulting in the large scale use of (now worthless) Soviet commemorative coins to defraud automated vending machines in Switzerland years after they have been demonetized.[9]

Starting in 1991 with the final year of the 1961 coin series, both kopeck and ruble coins began depicting the mint marks (М) for Moscow, and (Л) for Leningrad.

Banknotes

[edit]Banknotes were issued by the USSR State Treasury (Государственный казначейский билет, Gosudarstvenny kaznacheyskiy bilet) in denominations of 1, 3 and 5 rubles, and by the USSR State Bank (билет Государственного банка, Bilet gosudarstvennogo banka) in denominations of 10, 25, 50 and 100 rubles. Colors are similar to the previous series but notes were much smaller in size.

1989 Unreleased Soviet Rubles

[edit]After the failed project of making the 50th anniversary banknotes for 1967,[10] the projects for the 30 ruble in 1988 were worked out in Goznak. The first ruble that was projected as an example of the 1967 project, breaking with old Soviet tradition. They decided to put other faces which in the first note was Tsiolkovsky's statue. For unknown reasons it was cancelled and archived in the "failed projects" archive with barely any prints after a debate around the prototype of the note. At the same time they tried to adopt a more traditional 30 Soviet ruble banknote which replaced the whole face-project with the Kremlin Tower. Although the project was already started in 1988 and was finalized in 1989, it had some potential and intention to be adopted but the Gosbank decided to not put in practice and was cancelled. Even in 1988, a lot of projects were started with the Tsiolkovsky monument banknotes but were never recovered and was certainly rejected as a proposal and only the 30 note remained while other variations got lost.

"Central Bank of Russia" project (1990)

[edit]The whole concept was to adopt a new Soviet ruble under the "Central Bank of Russia" which is still questioned. Although, there aren't only one type of banknotes and some of these prototype notes were discovered in different places, even though its authenticity is still questioned as of one of the most outstanding banknotes of this (20, representing M.N Kutuzov)[11] series also becoming one of the most controversial ones because it was found in a professional banknote collector's album, as it was randomly discovered. The whole project was canceled because the name "Central Bank of Russia" and the different faces caused a lot of outrage as it was promoted as "Russian" and not Soviet, and was not promoting Lenin's head and tried to build up a totally whole new concept around the new 1991 series.[10]

1991 Forgotten Soviet banknote project

[edit]In 1989, designers sat at a table to draw a new type of Soviet banknote which represented buildings rather than people. Only the 1- and 2-ruble notes were designed. The 2-ruble note was designed in 1989 and could have been released in 1991. It was a very unusual sketch that combines the working man and the Kremlin as the whole unity of the country, the banknotes was drawn by V.K Nikitin. The 1-ruble note was designed back in 1989 by I.S Krylov and was planned to be released in 1991. The artist was chief of the artists of Goznak, one of the creators of the Soviet ruble banknotes between 1947 and 1991. He also painted a number of postage stamps in the same period.[12]

Seventh Soviet ruble, 1991–1993

[edit]The Monetary Reform of 1991 was carried out by Mikhail Gorbachev and was known also as the Pavlov Reform. It was the last of such in the Soviet Union and began on January 22, 1991. Its architect was Minister of Finance Valentin Pavlov, who also became the last prime minister of the Soviet Union. The details included a brief period to exchange old 1961-dated 50- and 100-ruble notes for new 1991 notes — for three days from 23 to 25 January (Wednesday to Friday) and with a specific limit of no more than Rbls 1,000 per person—the ability to exchange other notes considered in the special commissions to the end of March 1991. See Monetary reform in the Soviet Union, 1991.

Coins

[edit]In late 1991, a new coinage was issued as direct obligations of the USSR State Bank in denominations of 10 and 50 kopecks, and 1, 5 and 10 rubles. The 10-kopeck coin was struck in brass-plated steel, the 50-kopeck and 1- and 5-ruble coins, in cupro-nickel, and the 10-ruble coin bimetallic with an aluminium-bronze centre and a cupro-nickel-zinc ring. The series depicts an image of the Kremlin on the obverse rather than the Soviet state emblem. However, this coin series was extremely short-lived as the Soviet Union ceased to exist only months after its release. It did, however, continue to be used in several former Soviet republics including Russia and particularly Tajikistan for a short time after the union had ceased to exist out of necessity.

Banknotes

[edit]New 1991-dated banknotes were all issued as USSR State Bank notes (including the 1, 3, and 5-ruble denominations), with nearly identical colours and size for all denominations, but included more colour and heightened security features. The 25-ruble note was omitted from this series, but still remained legal tender; all 1961 notes apart from the demonetized 50- and 100-ruble denominations remained in circulation. An important modification of the design included the removal of the texts in languages of other Soviet republics (i.e. all texts were in Russian only) in the 1992 issues; all 1991 notes (in exception to the 2nd 1991 100-ruble banknote) contained all Soviet languages. In this series, 1-ruble notes were issued on 27 June 1991, 3-ruble notes on 3 November 1991, 5-ruble notes on 5 July 1991, 10-ruble notes on 10 July 1991, 50- and 100-ruble notes on 23 January 1991, 200-ruble notes on 29 October 1991, and 500-ruble notes on 24 December 1991. 1,000-ruble notes were issued in March 1992, after the Soviet collapse. New 1992-dated notes, similar in appearance to the 1991 issues, were printed in denominations of 50 to 1,000 rubles. bearing the Soviet state emblem and name. A notable exception was that the more-colourful Rbls 100. Notes of this series were still dated 1991 unlike the others.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, many newly independent republics chose to continue circulating Soviet rubles even after the introduction of the new Russian ruble in 1992.

1992 Soviet rubles

[edit]After the collapse of the Soviet Union, new banknotes were implemented using the old 1991 model even after the collapse. These are stamped with a denomination symbol and all languages of the former union were removed except Russian language. Even after the USSR ceased to exist, it was still titled as the money of the USSR. These were temporary issues as already in the same year, new notes were implemented. After the Monetary Reform of 1993, these notes were out of circulation and were free to exchange with the new 1993 issues.

Economic role

[edit]The Soviet Union ran a planned economy, where the government controlled prices and the exchange of currency. Thus the Soviet ruble did not function like a currency in a market economy, because mechanisms other than currency, such as centrally planned quotas, controlled the distribution of goods. Consequently, the ruble did not have the utility of a true currency; instead, it more resembled the scrip issued in a truck system. Soviet citizens could freely purchase a set of goods from state shops with rubles, but choice was limited and prices were always political decisions, having no direct connection to manufacturing cost. Bread and public transport were heavily subsidised, but wages were low and there were shortages of manufactured consumer goods, implementing hidden taxes.[13] It was common to hold large savings in rubles in the State Labor Savings Banks System of the USSR because credit was not available. Special rubles used in accounting were not exchangeable to cash, and were effectively different currency units pegged to the ruble. The currency was not freely exchangeable and its export was illegal. In bilateral trade, a separate, non-convertible "clearing ruble" credit was used.[14] There were separate shops (Beriozka) for purchasing goods obtained with hard currencies. However, Soviet citizens could not legally own foreign currency. Thus, if they legally received payment in foreign currency, they were forced to convert it to Vneshposyltorg cheques at a rate set by the government. These cheques could be spent at a Beriozka. The sudden transformation from a Soviet "non-currency" into a market currency contributed to the economic hardship following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991.[13][15][16]

Exchange rates

[edit]

The Soviet Union officially valued the ruble in the planned economy at an average of US$1.35 (or Rbl 0.74 per US dollar; see below) from 1971 to 1988. However, as the ruble was not internationally exchangeable and as Soviet citizens could not legally own foreign currency, rubles changed hands in the black market at an average of Rbls 4.14 per dollar in the same period 1971–88.[17] The opening up of the economy in the late 1980s under perestroika resulted in the recognition of more realistic exchange rates for the ruble, as follows:

- In November 1989 the ruble was devalued for foreign travel to a tourist rate of Rbls 6.26 per dollar (versus Rbl 0.6277 officially).[18]

- In November 1990 a new commercial exchange rate of Rbls 1.80 per dollar was introduced. During this time, however, black market dollars changed hands at 20 Rbls.[19]

- In April 1991, following the failed monetary reform of 1991, the tourist exchange rate was raised significantly to Rbls 27.60 per dollar, making the average monthly Soviet salary of Rbls 330 worth only $12 on the international market.[20]

- Further pain would continue later that year with the dollar changing hands at Rbls 35-40 on the black market and Rbls 45-70 in government auctions as of October 1991.[21]

- By early December 1991, just before the Soviet Union ceased to exist, the ruble had depreciated to nearly Rbls 100 to the dollar.[22]

Official exchange rates Soviet ruble of the time per United States dollar:[23]

| Date | Rbls of the time per US$ | US$ per Rbl of the time |

|---|---|---|

| 1924-01-01 | Rbls 2.2000 | $0.4545 |

| 1924-04-01 | Rbls 1.9405 | $0.5153 |

| 1927-01-01 | Rbls 1.9450 | $0.5141 |

| 1928-02-01 | Rbls 1.9434 | $0.5145 |

| 1933-04-01 | Rbls 1.9434 | $0.5145 |

| 1933-05-01 | Rbls 1.7474 | $0.5722 |

| 1934-01-01 | Rbls 1.2434 | $0.8042 |

| 1935-01-01 | Rbls 1.1509 | $0.8689 |

| 1936-01-01 | Rbls 1.1516 | $0.8684 |

| 1937-01-01 | Rbls 5.0400 | $0.1984 |

| 1937-07-19 | Rbls 5.3000 | $0.1887 |

| 1950-02-01 | Rbls 5.3000 | $0.1887 |

| 1950-03-01 | Rbls 4.0000 | $0.2500 |

| 1960-12-01 | Rbls 4.0000 | $0.2500 |

| 1961-01-01 | Rbl 0.9000 | $1.1111 |

| 1971-12-01 | Rbl 0.9000 | $1.1111 |

| 1972-01-01 | Rbl 0.8290 | $1.2063 |

| 1973-01-01 | Rbl 0.8260 | $1.2107 |

| 1974-01-01 | Rbl 0.7536 | $1.3270 |

| 1975-01-01 | Rbl 0.7300 | $1.3699 |

| 1976-01-01 | Rbl 0.7580 | $1.3193 |

| 1977-01-01 | Rbl 0.7420 | $1.3477 |

| 1978-01-01 | Rbl 0.7060 | $1.4164 |

| 1979-01-01 | Rbl 0.6590 | $1.5175 |

| 1980-01-03 | Rbl 0.6395 | $1.5637 |

| 1981-01-01 | Rbl 0.6750 | $1.4815 |

| 1982-01-01 | Rbl 0.7080 | $1.4124 |

| 1983-01-13 | Rbl 0.7070 | $1.4144 |

| 1984-01-01 | Rbl 0.7910 | $1.2642 |

| 1985-02-28 | Rbl 0.9200 | $1.0870 |

| 1986-01-01 | Rbl 0.7585 | $1.3184 |

| 1987-01-01 | Rbl 0.6700 | $1.4925 |

| 1988-01-06 | Rbl 0.5804 | $1.7229 |

| 1989-01-04 | Rbl 0.6059 | $1.6504 |

| 1990-01-03 | Rbl 0.6072 | $1.6469 |

| 1991-01-02 | Rbl 0.5605 | $1.7841 |

| 1991-02-13 | Rbl 0.5450 | $1.8349 |

| 1992-01-01 | Rbl 0.5549 | $1.8021 |

Replacement currencies in the former Soviet republics

[edit]Shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, local currencies were introduced in the newly independent states. Most of the new economies were weak and hence most of the currencies have undergone significant reforms since their introduction. In the very beginning of the post-Soviet economic transition, it was widely believed by ordinary people and monetary institutions (including the International Monetary Fund) that it was possible to maintain a common currency working for all or at least for some of the former Soviet Union's countries.[citation needed] The wish to preserve the strong trade relations between former Soviet republics was considered the most important goal.[citation needed]

During the first half of 1992, a monetary union with 15 independent states all using the ruble existed. Since it was clear that the situation would not last, each of them used their positions as "free-riders" to issue huge amounts of money in the form of credit (since Russia held the monopoly on printing banknotes and coins). As a result, some countries were issuing coupons in order to "protect" their markets from buyers from other states. [citation needed] This also started to cause massive inflation in the formerly high-valued currency. The Russian central bank responded in July 1992 by setting up restrictions on the flow of credit between Russia and other states. The final collapse of the "ruble zone" began with the exchange of banknotes by the Central Bank of Russia on Russian territory at the end of July 1993. As a result, other countries still in the ruble zone (Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Moldova, Armenia and Georgia) were "pushed out".[citation needed] By November 1993 all newly independent states had introduced their own currencies, with the exception of war-torn Tajikistan (May 1995) and unrecognized Transnistria (1994). Due to ruinous inflation in the former Soviet Republics, most of the successor currencies had to be redenominated at least once, with the notable exceptions of the Armenian dram, Estonian kroon, Kazakh tenge, and Kyrgyz som.

Details on the introduction of new currencies in the newly independent states are discussed below.

| Post-Soviet country |

First national currency (with new code) replacing the "Soviet ruble" (SUR) |

Conversion rate from SUR |

Date introduction for new currency | Date leaving the "ruble zone"[4] |

Future revaluation or currency replacement date, new replaced currency and rate[24] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armenia | Armenian dram (AMD) |

200 SUR = 1 AMD |

22 November 1993 | November 1993 | - |

| Azerbaijan | Second Azerbaijani manat (AZM) |

10 SUR = 1 AZM |

15 August 1992 | August 1993 | 1 January 2006: Third Azerbaijani manat (AZN) 5,000 AZM = 1 AZN |

| Belarus | Belarusian ruble (BYB) |

10 SUR = 1 BYB |

25 May 1992 | 26 July 1993 | 2000: Second Belarusian ruble (BYR) 1,000 BYB = 1 BYR 2016: Third Belarusian ruble (BYN) 10,000 BYR = 1 BYN |

| Estonia | Estonian kroon (EEK) |

10 SUR = 1 EEK |

20 June 1992 | 22 June 1992 | 1 January 2011: Euro (EUR) 15.6466 EEK = 1 EUR |

| Georgia | Georgian kuponi (GEK) |

1 SUR = 1 GEK |

8 April 1993 | 20 August 1993 | 20 October 1995: Georgian lari (GEL) 1,000,000 GEK = 1 GEL |

| Kazakhstan | Kazakh tenge (KZT) |

500 SUR = 1 KZT |

15 November 1993 | November 1993 | - |

| Kyrgyzstan | Kyrgyz som (KGS) |

200 SUR = 1 KGS |

10 May 1993 | 15 May 1993 | - |

| Latvia | Latvian ruble (LVR) |

1 SUR = 1 LVR |

7 May 1992 | 20 July 1992 | 5 March 1993: Latvian lats (LVL) 200 LVR = 1 LVL 1 January 2014: Euro (EUR) 0.702804 LVL = 1 EUR |

| Lithuania | Lithuanian talonas (LTT) |

10 SUR = 1 LTT |

1 May 1992 | 1 October 1992 | 26 June 1993: Lithuanian litas (LTL) 100 LTT = 1 LTL 1 January 2015: Euro (EUR) 3.4528 LTL = 1 EUR |

| Moldova | Moldovan cupon (MDC) |

1 SUR = 1 MDC |

10 June 1992 | July 1993 | 29 November 1993: Moldovan leu (MDL) 1,000 MDC = 1 MDL |

| Russia | First Russian ruble (RUR) |

1 SUR = 1 RUR |

14 July 1992 | August 1993 | 1 January 1998: Second Russian ruble (RUB) 1,000 RUR = 1 RUB |

| Tajikistan | Tajik ruble (TJR) |

100 SUR = 1 TJR |

10 May 1995 | January 1994 | 30 October 2000: Tajikistani somoni (TJS) 1,000 TJR = 1 TJS |

| Turkmenistan | First Turkmenistani manat (TMM) |

500 SUR = 1 TMM |

1 November 1993 | November 1993 | 1 January 2009: Second Turkmenistani manat (TMT) 5,000 TMM = 1 TMT |

| Ukraine | Kupono-karbovanets (UAK) |

1 SUR = 1 UAK |

12 January 1992 | November 1992 | 2 September 1996: Ukrainian hryvnia (UAH) 100,000 UAK = 1 UAH |

| Uzbekistan | Uzbek sum-kupon (UZC) |

1 SUR = 1 UZC |

15 November 1993 | 15 November 1993 | 1 July 1994: Uzbekistani sum (UZS) 1,000 UZC = 1 UZS |

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Balkema, A.A. (1992). Proceedings of the Tenth World Conference on Earthquake Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 9789054100607.

- ^ Szawlowski, Richard (1976). The system of the international organizations of the communist countries. BRILL. ISBN 9789028603356.

- ^ Agency, United States Central Intelligence, "Soviet Union", The World Factbook (1990), retrieved 2023-08-17

- ^ a b c d John Odling-Smee, Gonzalo Pastor. The IMF and the Ruble Area, 1991—1993 // IMF Working Paper, 2001 Archived 2015-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NSV Liidu valuutasüsteem ja esimesed ühisettevõtted" (in Estonian) Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b European Currency and Finance ... U.S. Government Printing Office. 1925.

- ^ An Economic History of the U.S.S.R. by Alec Nove (ISBN 0-14-021403-8), pp. 283, 310.

- ^ Bornstein, Morris (1961). "The Reform and Revaluation of the Ruble". The American Economic Review. 51 (1): 117–123. JSTOR 1818912.

- ^ "Mit alten Rubelmünzen Automaten am Zürcher HB geplündert". Swissinfo. 15 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30.

- ^ a b "Купюры советских рублей, которые были готовы к выпуску, пока что-то пошло не так". Mixnews (in Russian). 2021-10-04. Archived from the original on 2024-07-11. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ "Некоторые Советские купюры, о которых мало кто знает, но они были выпущены в оборот !". 9111.ru (in Russian). 22 December 2021. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ "Депутат объяснил, есть ли у военкоматов право на мобилизацию россиян". 9111.ru (in Russian). 22 March 2023. Retrieved 2023-03-23.

- ^ a b Online, WSI (18 August 2015). "Rahan arvottomuus - The Baltic Guide Online". balticguide.ee. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Idänkaupan loppu - Suomen ja Neuvostoliiton välinen erityinen kauppasuhde ja Suomen kauppapolitiikan odotushorisontti sen purkautuessa 1988–1991". helsinki.fi. 7 May 2018. Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Osband, Kent (7 May 2018). Pandora's Risk: Uncertainty at the Core of Finance. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231151726. Archived from the original on 15 March 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Susiluoto, Ilmari. Vilpittömän ilon valtakunta. Gummerus, Jyväskylä 2007. ISBN 978-951-20-7496-9. Pages 174–177, 180–181.

- ^ p19 https://helda.helsinki.fi/bof/bitstream/handle/123456789/12975/0392SA2.PDF Archived 2022-04-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Fein, Esther B.; Times, Special To the New York (1989-10-26). "Ruble Is Devalued in Some Cases; Step to Spur Soviet Economy Seen". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-08-17. Retrieved 2023-08-17.

- ^ "Dollars, Dollars Everywhere Amid Ruble Confusion". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ^ "Soviets Sharply Devalue Ruble in Move to Crush Currency Black Market". Los Angeles Times. 4 April 1991. Archived from the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ^ "WHEN IS A RUBLE NOT WORTH A RUBLE? - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2022-10-16. Retrieved 2021-10-12.

- ^ Schreck, Carl (2 December 2014). "Crash Course: The Ruble's Volatile Two Decades". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Archived from the original on 16 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2021.

- ^ "Archive". Central Bank of Russia. Archived from the original on 2013-02-03. Retrieved 2012-09-11.

- ^ ISO 4217

External links

[edit]- Leon Trotsky. The Revolution Betrayed. Chapter 4 – The Struggle for Productivity of Labor, associated with the issuence of the ruble, 1936

- A commercial site with some relevant historical information

- Catalog of USSR Banknotes from 1922

- Historical banknotes of the Soviet Union (incl. Banknotes of the successor States of the USSR) (in English, German, and French)