History of calculus

Calculus, originally called infinitesimal calculus, is a mathematical discipline focused on limits, continuity, derivatives, integrals, and infinite series. Many elements of calculus appeared in ancient Greece, then in China and the Middle East, and still later again in medieval Europe and in India. Infinitesimal calculus was developed in the late 17th century by Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz independently of each other. An argument over priority led to the Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy which continued until the death of Leibniz in 1716. The development of calculus and its uses within the sciences have continued to the present.

Etymology

[edit]In mathematics education, calculus denotes courses of elementary mathematical analysis, which are mainly devoted to the study of functions and limits. The word calculus is Latin for "small pebble" (the diminutive of calx, meaning "stone"), a meaning which still persists in medicine. Because such pebbles were used for counting out distances,[1] tallying votes, and doing abacus arithmetic, the word came to mean a method of computation. In this sense, it was used in English at least as early as 1672, several years prior to the publications of Leibniz and Newton.[2]

In addition to the differential calculus and integral calculus, the term is also used widely for naming specific methods of calculation. Examples of this include propositional calculus in logic, the calculus of variations in mathematics, process calculus in computing, and the felicific calculus in philosophy.

Early precursors of calculus

[edit]Ancient

[edit]

Egypt and Babylonia

[edit]The ancient period introduced some of the ideas that led to integral calculus, but does not seem to have developed these ideas in a rigorous and systematic way. Calculations of volumes and areas, one goal of integral calculus, can be found in the Egyptian Moscow papyrus (c. 1820 BC), but the formulas are only given for concrete numbers, some are only approximately true, and they are not derived by deductive reasoning.[3] Babylonians may have discovered the trapezoidal rule while doing astronomical observations of Jupiter.[4][5]

Greece

[edit]

From the age of Greek mathematics, Eudoxus (c. 408–355 BC) used the method of exhaustion, which foreshadows the concept of the limit, to calculate areas and volumes, while Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) developed this idea further, inventing heuristics which resemble the methods of integral calculus.[6] Greek mathematicians are also credited with a significant use of infinitesimals. Democritus is the first person recorded to consider seriously the division of objects into an infinite number of cross-sections, but his inability to rationalize discrete cross-sections with a cone's smooth slope prevented him from accepting the idea. At approximately the same time, Zeno of Elea discredited infinitesimals further by his articulation of the paradoxes which they seemingly create.

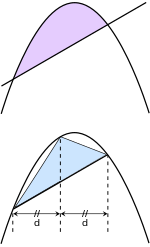

Archimedes developed this method further, while also inventing heuristic methods which resemble modern day concepts somewhat in his The Quadrature of the Parabola, The Method, and On the Sphere and Cylinder.[7] It should not be thought that infinitesimals were put on a rigorous footing during this time, however. Only when it was supplemented by a proper geometric proof would Greek mathematicians accept a proposition as true. It was not until the 17th century that the method was formalized by Cavalieri as the method of Indivisibles and eventually incorporated by Newton into a general framework of integral calculus. Archimedes was the first to find the tangent to a curve other than a circle, in a method akin to differential calculus. While studying the spiral, he separated a point's motion into two components, one radial motion component and one circular motion component, and then continued to add the two component motions together, thereby finding the tangent to the curve.[8]

China

[edit]The method of exhaustion was independently invented in China by Liu Hui in the 4th century AD in order to find the area of a circle.[9] In the 5th century, Zu Chongzhi established a method that would later be called Cavalieri's principle to find the volume of a sphere.[10]

Medieval

[edit]Middle East

[edit]

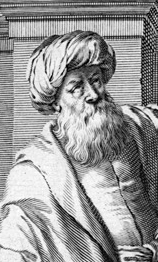

In the Middle East, Hasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (c. 965 – c. 1040 AD) derived a formula for the sum of fourth powers. He used the results to carry out what would now be called an integration, where the formulas for the sums of integral squares and fourth powers allowed him to calculate the volume of a paraboloid.[11] Roshdi Rashed has argued that the 12th century mathematician Sharaf al-Dīn al-Tūsī must have used the derivative of cubic polynomials in his Treatise on Equations. Rashed's conclusion has been contested by other scholars, who argue that he could have obtained his results by other methods which do not require the derivative of the function to be known.[12]

India

[edit]Evidence suggests Bhāskara II was acquainted with some ideas of differential calculus.[13] Bhāskara also goes deeper into the 'differential calculus' and suggests the differential coefficient vanishes at an extremum value of the function, indicating knowledge of the concept of 'infinitesimals'.[14] There is evidence of an early form of Rolle's theorem in his work. The modern formulation of Rolle's theorem states that if , then for some with . In his astronomical work, Bhāskara gives a result that looks like a precursor to infinitesimal methods: if then . This leads to the derivative of the sine function, although he did not develop the notion of a derivative.[15]

Some ideas on calculus later appeared in Indian mathematics, at the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics.[11] Madhava of Sangamagrama in the 14th century, and later mathematicians of the Kerala school, stated components of calculus such as the Taylor series and infinite series approximations.[16] However, they did not combine many differing ideas under the two unifying themes of the derivative and the integral, show the connection between the two, and turn calculus into the powerful problem-solving tool we have today.[11]

Europe

[edit]The mathematical study of continuity was revived in the 14th century by the Oxford Calculators and French collaborators such as Nicole Oresme. They proved the "Merton mean speed theorem": that a uniformly accelerated body travels the same distance as a body with uniform speed whose speed is half the final velocity of the accelerated body.[17]

Modern precursors

[edit]Integrals

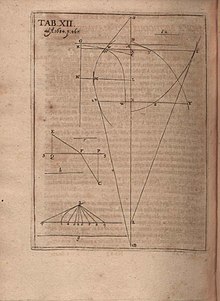

[edit]Johannes Kepler's work Stereometrica Doliorum published in 1615 formed the basis of integral calculus.[18] Kepler developed a method to calculate the area of an ellipse by adding up the lengths of many radii drawn from a focus of the ellipse.[19]

A significant work was a treatise inspired by Kepler's methods[19] published in 1635 by Bonaventura Cavalieri on his method of indivisibles. He argued that volumes and areas should be computed as the sums of the volumes and areas of infinitesimally thin cross-sections. He discovered Cavalieri's quadrature formula which gave the area under the curves xn of higher degree. This had previously been computed in a similar way for the parabola by Archimedes in The Method, but this treatise is believed to have been lost in the 13th century, and was only rediscovered in the early 20th century, and so would have been unknown to Cavalieri. Cavalieri's work was not well respected since his methods could lead to erroneous results, and the infinitesimal quantities he introduced were disreputable at first.

Torricelli extended Cavalieri's work to other curves such as the cycloid, and then the formula was generalized to fractional and negative powers by Wallis in 1656. In a 1659 treatise, Fermat is credited with an ingenious trick for evaluating the integral of any power function directly.[20] Fermat also obtained a technique for finding the centers of gravity of various plane and solid figures, which influenced further work in quadrature.

Derivatives

[edit]In the 17th century, European mathematicians Isaac Barrow, René Descartes, Pierre de Fermat, Blaise Pascal, John Wallis and others discussed the idea of a derivative. In particular, in Methodus ad disquirendam maximam et minima and in De tangentibus linearum curvarum distributed in 1636, Fermat introduced the concept of adequality, which represented equality up to an infinitesimal error term.[21] This method could be used to determine the maxima, minima, and tangents to various curves and was closely related to differentiation.[22]

Isaac Newton would later write that his own early ideas about calculus came directly from "Fermat's way of drawing tangents."[23]

Fundamental theorem of calculus

[edit]The formal study of calculus brought together Cavalieri's infinitesimals with the calculus of finite differences developed in Europe at around the same time, and Fermat's adequality. The combination was achieved by John Wallis, Isaac Barrow, and James Gregory, the latter two proving predecessors to the second fundamental theorem of calculus around 1670.[24][25]

James Gregory, influenced by Fermat's contributions both to tangency and to quadrature, was then able to prove a restricted version of the second fundamental theorem of calculus, that integrals can be computed using any of a function's antiderivatives.[26][27]

The first full proof of the fundamental theorem of calculus was given by Isaac Barrow.[28]: p.61 when arc ME ~ arc NH at point of tangency F fig.26 [29]

Other developments

[edit]

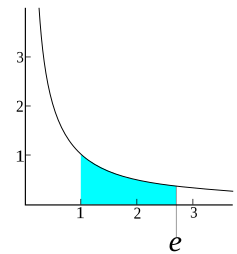

One prerequisite to the establishment of a calculus of functions of a real variable involved finding an antiderivative for the rational function This problem can be phrased as quadrature of the rectangular hyperbola xy = 1. In 1647 Gregoire de Saint-Vincent noted that the required function F satisfied so that a geometric sequence became, under F, an arithmetic sequence. A. A. de Sarasa associated this feature with contemporary algorithms called logarithms that economized arithmetic by rendering multiplications into additions. So F was first known as the hyperbolic logarithm. After Euler exploited e = 2.71828..., and F was identified as the inverse function of the exponential function, it became the natural logarithm, satisfying

The first proof of Rolle's theorem was given by Michel Rolle in 1691 using methods developed by the Dutch mathematician Johann van Waveren Hudde.[30] The mean value theorem in its modern form was stated by Bernard Bolzano and Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857) also after the founding of modern calculus. Important contributions were made by Barrow, Huygens, and many others.

Barrow has been credited by some authors as having invented calculus, however, Swiss mathematician Florian Cajori notes that while Barrow did work out a set of "geometric theorems suggesting to us constructions by which we can find lines, areas and volumes whose magnitudes are ordinarily found by the analytical processes of the calculus", he did not create "what by common agreement of mathematicians has been designated by the term differential and integral calculus", and further notes that "Two processes yielding equivalent results are not necessarily the same". Cajori finishes with stating that "The invention belongs rightly belongs to Newton and Leibniz".[31]

Newton and Leibniz

[edit]

Before Newton and Leibniz, the word "calculus" referred to any body of mathematics, but in the following years, "calculus" became a popular term for a field of mathematics based upon their insights.[32] Newton and Leibniz, building on this work, independently developed the surrounding theory of infinitesimal calculus in the late 17th century. Also, Leibniz did a great deal of work with developing consistent and useful notation and concepts. Newton provided some of the most important applications to physics, especially of integral calculus.

By the middle of the 17th century, European mathematics had changed its primary repository of knowledge. In comparison to the last century which maintained Hellenistic mathematics as the starting point for research, Newton, Leibniz and their contemporaries increasingly looked towards the works of more modern thinkers.[33]

Newton came to calculus as part of his investigations in physics and geometry. He viewed calculus as the scientific description of the generation of motion and magnitudes. In comparison, Leibniz focused on the tangent problem and came to believe that calculus was a metaphysical explanation of change. Importantly, the core of their insight was the formalization of the inverse properties between the integral and the differential of a function. This insight had been anticipated by their predecessors, but they were the first to conceive calculus as a system in which new rhetoric and descriptive terms were created.[34]

Newton

[edit]Newton completed no definitive publication formalizing his fluxional calculus; rather, many of his mathematical discoveries were transmitted through correspondence, smaller papers or as embedded aspects in his other definitive compilations, such as the Principia and Opticks. Newton would begin his mathematical training as the chosen heir of Isaac Barrow in Cambridge. His aptitude was recognized early and he quickly learned the current theories. By 1664 Newton had made his first important contribution by advancing the binomial theorem, which he had extended to include fractional and negative exponents. Newton succeeded in expanding the applicability of the binomial theorem by applying the algebra of finite quantities in an analysis of infinite series. He showed a willingness to view infinite series not only as approximate devices, but also as alternative forms of expressing a term.[35]

Many of Newton's critical insights occurred during the plague years of 1665–1666,[36] which he later described as, "the prime of my age for invention and minded mathematics and [natural] philosophy more than at any time since." It was during his plague-induced isolation that the first written conception of fluxionary calculus was recorded in the unpublished De Analysi per Aequationes Numero Terminorum Infinitas. In this paper, Newton determined the area under a curve by first calculating a momentary rate of change and then extrapolating the total area. He began by reasoning about an indefinitely small triangle whose area is a function of x and y. He then reasoned that the infinitesimal increase in the abscissa will create a new formula where x = x + o (importantly, o is the letter, not the digit 0). He then recalculated the area with the aid of the binomial theorem, removed all quantities containing the letter o and re-formed an algebraic expression for the area. Significantly, Newton would then "blot out" the quantities containing o because terms "multiplied by it will be nothing in respect to the rest".

At this point Newton had begun to realize the central property of inversion. He had created an expression for the area under a curve by considering a momentary increase at a point. In effect, the fundamental theorem of calculus was built into his calculations. While his new formulation offered incredible potential, Newton was well aware of its logical limitations at the time. He admits that "errors are not to be disregarded in mathematics, no matter how small" and that what he had achieved was "shortly explained rather than accurately demonstrated".

In an effort to give calculus a more rigorous explication and framework, Newton compiled in 1671 the Methodus Fluxionum et Serierum Infinitarum. In this book, Newton's strict empiricism shaped and defined his fluxional calculus. He exploited instantaneous motion and infinitesimals informally. He used math as a methodological tool to explain the physical world. The base of Newton's revised calculus became continuity; as such he redefined his calculations in terms of continual flowing motion. For Newton, variable magnitudes are not aggregates of infinitesimal elements, but are generated by the indisputable fact of motion. As with many of his works, Newton delayed publication. Methodus Fluxionum was not published until 1736.[37]

Newton attempted to avoid the use of the infinitesimal by forming calculations based on ratios of changes. In the Methodus Fluxionum he defined the rate of generated change as a fluxion, which he represented by a dotted letter, and the quantity generated he defined as a fluent. For example, if and are fluents, then and are their respective fluxions. This revised calculus of ratios continued to be developed and was maturely stated in the 1676 text De Quadratura Curvarum where Newton came to define the present day derivative as the ultimate ratio of change, which he defined as the ratio between evanescent increments (the ratio of fluxions) purely at the moment in question. Essentially, the ultimate ratio is the ratio as the increments vanish into nothingness. Importantly, Newton explained the existence of the ultimate ratio by appealing to motion:[38]

For by the ultimate velocity is meant that, with which the body is moved, neither before it arrives at its last place, when the motion ceases nor after but at the very instant when it arrives... the ultimate ratio of evanescent quantities is to be understood, the ratio of quantities not before they vanish, not after, but with which they vanish

Newton developed his fluxional calculus in an attempt to evade the informal use of infinitesimals in his calculations.

Leibniz

[edit]

While Newton began development of his fluxional calculus in 1665–1666 his findings did not become widely circulated until later. In the intervening years Leibniz also strove to create his calculus. In comparison to Newton who came to math at an early age, Leibniz began his rigorous math studies with a mature intellect. He was a polymath, and his intellectual interests and achievements involved metaphysics, law, economics, politics, logic, and mathematics. In order to understand Leibniz's reasoning in calculus his background should be kept in mind. Particularly, his metaphysics which described the universe as a Monadology, and his plans of creating a precise formal logic whereby, "a general method in which all truths of the reason would be reduced to a kind of calculation".[39]

In 1672, Leibniz met the mathematician Huygens who convinced Leibniz to dedicate significant time to the study of mathematics. By 1673 he had progressed to reading Pascal's Traité des sinus du quart de cercle and it was during his largely autodidactic research that Leibniz said "a light turned on". Like Newton, Leibniz saw the tangent as a ratio but declared it as simply the ratio between ordinates and abscissas. He continued this reasoning to argue that the integral was in fact the sum of the ordinates for infinitesimal intervals in the abscissa; in effect, the sum of an infinite number of rectangles. From these definitions the inverse relationship or differential became clear and Leibniz quickly realized the potential to form a whole new system of mathematics. Where Newton over the course of his career used several approaches in addition to an approach using infinitesimals, Leibniz made this the cornerstone of his notation and calculus.[40][41]

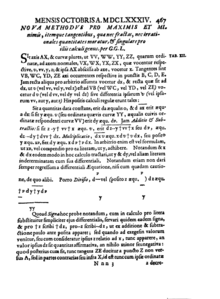

In the manuscripts of 25 October to 11 November 1675, Leibniz recorded his discoveries and experiments with various forms of notation. He was acutely aware of the notational terms used and his earlier plans to form a precise logical symbolism became evident. Eventually, Leibniz denoted the infinitesimal increments of abscissas and ordinates dx and dy, and the summation of infinitely many infinitesimally thin rectangles as a long s (∫ ), which became the present integral symbol .

While Leibniz's notation is used by modern mathematics, his logical base was different from our current one. Leibniz embraced infinitesimals and wrote extensively so as, "not to make of the infinitely small a mystery, as had Pascal."[42] According to Gilles Deleuze, Leibniz's zeroes "are nothings, but they are not absolute nothings, they are nothings respectively" (quoting Leibniz' text "Justification of the calculus of infinitesimals by the calculus of ordinary algebra").[43] Alternatively, he defines them as, "less than any given quantity". For Leibniz, the world was an aggregate of infinitesimal points and the lack of scientific proof for their existence did not trouble him. Infinitesimals to Leibniz were ideal quantities of a different type from appreciable numbers. The truth of continuity was proven by existence itself. For Leibniz the principle of continuity and thus the validity of his calculus was assured. Three hundred years after Leibniz's work, Abraham Robinson showed that using infinitesimal quantities in calculus could be given a solid foundation.[44]

Legacy

[edit]The rise of calculus stands out as a unique moment in mathematics. Calculus is the mathematics of motion and change, and as such, its invention required the creation of a new mathematical system. Importantly, Newton and Leibniz did not create the same calculus and they did not conceive of modern calculus. While they were both involved in the process of creating a mathematical system to deal with variable quantities their elementary base was different. For Newton, change was a variable quantity over time and for Leibniz it was the difference ranging over a sequence of infinitely close values. Notably, the descriptive terms each system created to describe change was different.

Historically, there was much debate over whether it was Newton or Leibniz who first "invented" calculus. This argument, the Leibniz and Newton calculus controversy, involving Leibniz, who was German, and the Englishman Newton, led to a rift in the European mathematical community lasting over a century. Leibniz was the first to publish his investigations; however, it is well established that Newton had started his work several years prior to Leibniz and had already developed a theory of tangents by the time Leibniz became interested in the question. It is not known how much this may have influenced Leibniz. The initial accusations were made by students and supporters of the two great scientists at the turn of the century, but after 1711 both of them became personally involved, accusing each other of plagiarism.

The priority dispute had an effect of separating English-speaking mathematicians from those in continental Europe for many years. Only in the 1820s, due to the efforts of the Analytical Society, did Leibnizian analytical calculus become accepted in England. Today, both Newton and Leibniz are given credit for independently developing the basics of calculus. It is Leibniz, however, who is credited with giving the new discipline the name it is known by today: "calculus". Newton's name for it was "the science of fluents and fluxions".

While neither of the two offered convincing logical foundations for their calculus according to mathematician Carl B. Boyer, Newton came the closest, with his best attempt coming in Principia, where he described his idea of "prime and ultimate ratios" and came extraordinarily close to the limit, and his ratio of velocities corresponded to a single real number, which would not be fully defined until the late nineteenth century.[45] On the other hand, the calculus of Leibniz was from a "logical point of view, distinctly inferior to that of Newton, for it never transcended the view of as a quotient of infinitely small changes or differences in y and x."[45] However, heuristically, it was a success, despite being a "failure" from a logical point of view.[45]

The work of both Newton and Leibniz is reflected in the notation used today. Newton introduced the notation for the derivative of a function f.[46] Leibniz introduced the symbol for the integral and wrote the derivative of a function y of the variable x as , both of which are still in use.

Since the time of Leibniz and Newton, many mathematicians have contributed to the continuing development of calculus. One of the first and most complete works on both infinitesimal and integral calculus was written in 1748 by Maria Gaetana Agnesi.[47][48]

Developments

[edit]Calculus of variations

[edit]The calculus of variations may be said to begin with a problem of Johann Bernoulli (1696). It immediately occupied the attention of Jakob Bernoulli but Leonhard Euler first elaborated the subject. His contributions began in 1733, and his Elementa Calculi Variationum gave to the science its name. Joseph Louis Lagrange contributed extensively to the theory, and Adrien-Marie Legendre (1786) laid down a method, not entirely satisfactory, for the discrimination of maxima and minima. To this discrimination Brunacci (1810), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1829), Siméon Denis Poisson (1831), Mikhail Vasilievich Ostrogradsky (1834), and Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi (1837) have been among the contributors. An important general work is that of Sarrus (1842) which was condensed and improved by Augustin Louis Cauchy (1844). Other valuable treatises and memoirs have been written by Strauch (1849), Jellett (1850), Otto Hesse (1857), Alfred Clebsch (1858), and Carll (1885), but perhaps the most important work of the century is that of Karl Weierstrass. His course on the theory may be asserted to be the first to place calculus on a firm and rigorous foundation.

Operational methods

[edit]Antoine Arbogast (1800) was the first to separate the symbol of operation from that of quantity in a differential equation. Francois-Joseph Servois (1814) seems to have been the first to give correct rules on the subject. Charles James Hargreave (1848) applied these methods in his memoir on differential equations, and George Boole freely employed them. Hermann Grassmann and Hermann Hankel made great use of the theory, the former in studying equations, the latter in his theory of complex numbers.

Integrals

[edit]Niels Henrik Abel seems to have been the first to consider in a general way the question as to what differential equations can be integrated in a finite form by the aid of ordinary functions, an investigation extended by Liouville. Cauchy early undertook the general theory of determining definite integrals, and the subject has been prominent during the 19th century. Frullani integrals, David Bierens de Haan's work on the theory and his elaborate tables, Lejeune Dirichlet's lectures embodied in Meyer's treatise, and numerous memoirs of Legendre, Poisson, Plana, Raabe, Sohncke, Schlömilch, Elliott, Leudesdorf and Kronecker are among the noteworthy contributions.

Eulerian integrals were first studied by Euler and afterwards investigated by Legendre, by whom they were classed as Eulerian integrals of the first and second species, as follows:

although these were not the exact forms of Euler's study.

If n is a positive integer:

but the integral converges for all positive real and defines an analytic continuation of the factorial function to all of the complex plane except for poles at zero and the negative integers. To it Legendre assigned the symbol , and it is now called the gamma function. Besides being analytic over positive reals , also enjoys the uniquely defining property that is convex, which aesthetically justifies this analytic continuation of the factorial function over any other analytic continuation. To the subject Lejeune Dirichlet has contributed an important theorem (Liouville, 1839), which has been elaborated by Liouville, Catalan, Leslie Ellis, and others. Raabe (1843–44), Bauer (1859), and Gudermann (1845) have written about the evaluation of and . Legendre's great table appeared in 1816.

Applications

[edit]The application of the infinitesimal calculus to problems in physics and astronomy was contemporary with the origin of the science. All through the 18th century these applications were multiplied, until at its close Laplace and Lagrange had brought the whole range of the study of forces into the realm of analysis. To Lagrange (1773) we owe the introduction of the theory of the potential into dynamics, although the name "potential function" and the fundamental memoir of the subject are due to Green (1827, printed in 1828). The name "potential" is due to Gauss (1840), and the distinction between potential and potential function to Clausius. With its development are connected the names of Lejeune Dirichlet, Riemann, von Neumann, Heine, Kronecker, Lipschitz, Christoffel, Kirchhoff, Beltrami, and many of the leading physicists of the century.

It is impossible in this article to enter into the great variety of other applications of analysis to physical problems. Among them are the investigations of Euler on vibrating chords; Sophie Germain on elastic membranes; Poisson, Lamé, Saint-Venant, and Clebsch on the elasticity of three-dimensional bodies; Fourier on heat diffusion; Fresnel on light; Maxwell, Helmholtz, and Hertz on electricity; Hansen, Hill, and Gyldén on astronomy; Maxwell on spherical harmonics; Lord Rayleigh on acoustics; and the contributions of Lejeune Dirichlet, Weber, Kirchhoff, F. Neumann, Lord Kelvin, Clausius, Bjerknes, MacCullagh, and Fuhrmann to physics in general. The labors of Helmholtz should be especially mentioned, since he contributed to the theories of dynamics, electricity, etc., and brought his great analytical powers to bear on the fundamental axioms of mechanics as well as on those of pure mathematics.

Furthermore, infinitesimal calculus was introduced into the social sciences, starting with Neoclassical economics. Today, it is a valuable tool in mainstream economics.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ See, for example:

- "history - Were metered taxis busy roaming Imperial Rome?". Skeptics Stack Exchange. 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2022-02-13.

- Cousineau, Phil (2010-03-15). Wordcatcher: An Odyssey into the World of Weird and Wonderful Words. Simon and Schuster. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-57344-550-4. OCLC 811492876.

- ^ "calculus". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Kline, Morris (1990-08-16). Mathematical thought from ancient to modern times. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. pp. 18–21. ISBN 978-0-19-506135-2.

- ^ Ossendrijver, Mathieu (29 January 2016). "Ancient Babylonian astronomers calculated Jupiter's position from the area under a time-velocity graph". Science. 351 (6272): 482–484. Bibcode:2016Sci...351..482O. doi:10.1126/science.aad8085. PMID 26823423. S2CID 206644971.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (2016). "Signs of Modern Astronomy Seen in Ancient Babylon". New York Times.

- ^ Archimedes, Method, in The Works of Archimedes ISBN 978-0-521-66160-7

- ^ MathPages — Archimedes on Spheres & Cylinders Archived 2010-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1991). "Archimedes of Syracuse". A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Wiley. pp. 127. ISBN 978-0-471-54397-8.

Greek mathematics sometimes has been described as essentially static, with little regard for the notion of variability; but Archimedes, in his study of the spiral, seems to have found the tangent to a curve through kinematic considerations akin to differential calculus. Thinking of a point on the spiral 1=r = aθ as subjected to a double motion — a uniform radial motion away from the origin of coordinates and a circular motion about the origin — he seems to have found (through the parallelogram of velocities) the direction of motion (hence of the tangent to the curve) by noting the resultant of the two component motions. This appears to be the first instance in which a tangent was found to a curve other than a circle.

Archimedes' study of the spiral, a curve that he ascribed to his friend Conon of Alexandria, was part of the Greek search for the solution of the three famous problems. - ^ Dun, Liu; Fan, Dainian; Cohen, Robert Sonné (1966). A comparison of Archimdes' and Liu Hui's studies of circles. Chinese studies in the history and philosophy of science and technology. Vol. 130. Springer. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-7923-3463-7., Chapter, p. 279

- ^ Zill, Dennis G.; Wright, Scott; Wright, Warren S. (2009). Calculus: Early Transcendentals (3 ed.). Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. xxvii. ISBN 978-0-7637-5995-7. Extract of page 27

- ^ a b c Katz, Victor J. (June 1995). "Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India". Mathematics Magazine. 68 (3): 163–174. doi:10.1080/0025570X.1995.11996307. ISSN 0025-570X. JSTOR 2691411.

- ^ Berggren, J. L.; Al-Tūsī, Sharaf Al-Dīn; Rashed, Roshdi; Al-Tusi, Sharaf Al-Din (April 1990). "Innovation and Tradition in Sharaf al-Dīn al-Ṭūsī's Muʿādalāt". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 110 (2): 304–309. doi:10.2307/604533. JSTOR 604533.

- ^ 50 Timeless Scientists von K.Krishna Murty

- ^ Shukla, Kripa Shankar (1984). "Use of Calculus in Hindu Mathematics". Indian Journal of History of Science. 19: 95–104.

- ^ Cooke, Roger (1997). "The Mathematics of the Hindus". The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. pp. 213–215. ISBN 0-471-18082-3.

- ^ Indian mathematics

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. (1959). "III. Medieval Contributions". A History of the Calculus and Its Conceptual Development. Dover. pp. 79–89. ISBN 978-0-486-60509-8.

- ^ "Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws and Times". NASA. 24 September 2016. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-10.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 14 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 537.

- ^ Paradís, Jaume; Pla, Josep; Viader, Pelagrí. "Fermat's Treatise On Quadrature: A New Reading" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-01-07. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Weil, André (1984). Number theory: An approach through History from Hammurapi to Legendre. Boston: Birkhauser Boston. p. 28. ISBN 0-8176-4565-9.

- ^ Pellegrino, Dana. "Pierre de Fermat". Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ^ Simmons, George F. (2007). Calculus Gems: Brief Lives and Memorable Mathematics. Mathematical Association of America. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-88385-561-4.

- ^ Hollingdale, Stuart (1991). "Review of Before Newton: The Life and Times of Isaac Barrow". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 45 (2): 277–279. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1991.0027. ISSN 0035-9149. JSTOR 531707. S2CID 165043307.

The most interesting to us are Lectures X-XII, in which Barrow comes close to providing a geometrical demonstration of the fundamental theorem of the calculus... He did not realize, however, the full significance of his results, and his rejection of algebra means that his work must remain a piece of mid-17th century geometrical analysis of mainly historic interest.

- ^ Bressoud, David M. (2011). "Historical Reflections on Teaching the Fundamental Theorem of Integral Calculus". The American Mathematical Monthly. 118 (2): 99. doi:10.4169/amer.math.monthly.118.02.099. S2CID 21473035.

- ^ See, e.g., Marlow Anderson, Victor J. Katz, Robin J. Wilson, Sherlock Holmes in Babylon and Other Tales of Mathematical History, Mathematical Association of America, 2004, p. 114.

- ^ Gregory, James (1668). Geometriae Pars Universalis. Museo Galileo: Patavii: typis heredum Pauli Frambotti.

- ^ The geometrical lectures of Isaac Barrow, translated, with notes and proofs, and a discussion on the advance made therein on the work of his predecessors in the infinitesimal calculus. Chicago: Open Court. 1916. Translator: J. M. Child (1916)

- ^ Review of J.M. Child's translation (1916) The geometrical lectures of Isaac Barrow reviewer: Arnold Dresden (Jun 1918) p.454 Barrow has the fundamental theorem of calculus

- ^ Johnston, William; McAllister, Alex (2009). A Transition to Advanced Mathematics: A Survey Course. Oxford University Press US. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-19-531076-4., Chapter 4, p. 333

- ^ Cajori, Florian; Child, J. M. (1919). "Who Was the First Inventor of the Calculus?". The American Mathematical Monthly. 26 (1): 15. doi:10.2307/2974042.

- ^ Reyes 2004, p. 160

- ^ Such as Kepler, Descartes, Fermat, Pascal and Wallis. Calinger 1999, p. 556

- ^ Foremost among these was Barrow who had created formulas for specific cases and Fermat who created a similar definition for the derivative. For more information; Boyer 184

- ^ Calinger 1999, p. 610

- ^ Newton, Isaac. "Waste Book". Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- ^ Eves, Howard. An introduction to the history of mathematics, 6th edition. p. 400.

- ^ Principia, Florian Cajori 8

- ^ "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2020.

- ^ "Gottfried Leibniz - Biography".

- ^ "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz | Biography & Facts".

- ^ Boyer, Carl (1939). The History of the Calculus and Its Conceptual Development. Courier Corporation. ISBN 9780486605098.

- ^ Deleuze, Gilles. "DELEUZE / LEIBNIZ Cours Vincennes - 22/04/1980". Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ "The Calculus of Infinitesimals".

- ^ a b c Boyer, Carl B. (1970). "The History of the Calculus". The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal. 1 (1): 60–86. doi:10.2307/3027118. ISSN 0049-4925. JSTOR 3027118.

- ^ The use of prime to denote the derivative, is due to Lagrange.

- ^ Allaire, Patricia R. (2007). Foreword. A Biography of Maria Gaetana Agnesi, an Eighteenth-century Woman Mathematician. By Cupillari, Antonella (illustrated ed.). Edwin Mellen Press. p. iii. ISBN 978-0-7734-5226-8.

- ^ Unlu, Elif (April 1995). "Maria Gaetana Agnesi". Agnes Scott College.

Further reading

[edit]- Roero, C.S. (2005). "Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, first three papers on the calculus (1684, 1686, 1693)". In Grattan-Guinness, I. (ed.). Landmark writings in Western mathematics 1640–1940. Elsevier. pp. 46–58. ISBN 978-0-444-50871-3. Zbl 1090.01002.

- Roero, C.S. (1983). "Jakob Bernoulli, attentive student of the work of Archimedes: marginal notes to the edition of Barrow". Boll. Storia Sci. Mat. 3 (1): 77–125. ISSN 0392-4432.

- Boyer, Carl (1959) [1949]. The History of the Calculus and its Conceptual Development. Dover. ISBN 0-486-60509-4. OCLC 643872. Zbl 0095.00302. Republication of a 1939 book (2nd printing in 1949) with a different title.

- Calinger, Ronald (1999). A Contextual History of Mathematics. Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0-02-318285-3. OCLC 40479696.

- Reyes, Mitchell (2004). "The Rhetoric in Mathematics: Newton, Leibniz, the Calculus, and the Rhetorical Force of the Infinitesimal". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 90 (2): 159–184. doi:10.1080/0033563042000227427. S2CID 145802382.

- Grattan-Guinness, Ivor (2000). The Rainbow of Mathematics : A History of the Mathematical Sciences. W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-32030-5. OCLC 44155819. Zbl 0876.01003.

- Ch. 5 The age of trigonometry : Europe, 1540–1660

- Ch. 6 The calculus and its consequences, 1660–1750

- Hoffman, Ruth Irene (1937). On the development and use of the concepts of the infinitesimal calculus before Newton and Leibniz (M.A.). University of Colorado. OCLC 48160073.